The Local War Memorials

Introduction

Today the parish or village war memorial is a prominent feature of practically every city, town or village in Britain. Estimates about how many there are vary between 50,000 and 100,000 and although that is a huge variation it is a reminder that the building of the war memorials in each community was very much a local effort undertaken by local voluntary committees without any central direction often with no assistance from the local authority and definitely with none from the national government. The four war memorials described in this article – Renton, Luss, Kilmaronock and what was built as Bonhill Parish War Memorial but which is now usually referred as the Alexandria War Memorial or Cenotaph were all built by voluntary effort as we shall see.

Today the parish or village war memorial is a prominent feature of practically every city, town or village in Britain. Estimates about how many there are vary between 50,000 and 100,000 and although that is a huge variation it is a reminder that the building of the war memorials in each community was very much a local effort undertaken by local voluntary committees without any central direction often with no assistance from the local authority and definitely with none from the national government. The four war memorials described in this article – Renton, Luss, Kilmaronock and what was built as Bonhill Parish War Memorial but which is now usually referred as the Alexandria War Memorial or Cenotaph were all built by voluntary effort as we shall see.

In Britain the building of memorials to the men who had died fighting for their country only started on any scale after World War One (WW1). Until then, Great Britain had virtually ignored its war dead and accorded them no respect at all, particularly the ordinary soldier. This was perhaps not so surprising when one considers how the ordinary serving soldier or sailor was treated when they were alive be it in peace time or in war - officers were a different matter altogether. Take the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 for instance: the bodies of the British other ranks killed in the Battle – over 5,000 British soldiers were killed at Waterloo – were piled up in heaps and then dumped into common pits with no attempt made to identify who was in each pit. It was not until 1889 that Queen Victoria ordered that the dead of Waterloo be exhumed and re-interred with due military honours in the Evere Cemetery in Brussels.

The Crimean War would have been no different had it not been for the work of Florence Nightingale. In her military hospital at Scutari thousands of men died, as many from disease as war wounds, and they had to be buried somewhere nearby. So the first British military cemetery was created, not by the Army authorities, but by an uninvited woman whose very presence was an anathema to many of the British Army commanders in Crimea. However, the government did not accept any responsibility for the Scutari cemetery’s maintenance and a scandal erupted 20 years later when its state of disrepair was reported back in Britain. In the whole of Britain there was one solitary memorial to the dead of the Crimean War. It is in London and this Memorial commemorated only the Brigade of Guards. The heroic Thin Red Line or the Charge of the Light Brigade, military fiasco as it was, might have been good for patriotic propaganda and poems but no memorial was erected to the participants or victims.

The Boer War was much the same. Graves were neglected and although there were some regimental and local memorials there was no acceptance by the Army or the government that some public exhibition of respect for those who had fought or died was in order. Again, the neglect of graves of the war dead became a public scandal and although it made little difference to official thinking, it did have a profound affect on one man who had served in the South African government at the time.

His name was Sir Frederick Ware and, unusually perhaps, he was both a visionary and a doer who was to make a huge impact on Britain’s approach to according proper respect to its war dead in WW1 and since. His initial efforts in France at the beginning of WW1 were both voluntary and personal but laid the foundation for how the government and the nation came to treat its war dead both on the battlefield and back home in local communities. In his work on Battlefield Memorials and War Cemeteries he was greatly assisted by the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens and we shall hear more of them later. Although they did not directly initiate or participate in campaigns for local memorials, their work in France, Flanders and elsewhere was a major influence on the emergence of the tens of thousands of projects to build local Memorials to the Fallen.

The First National War Memorial, Whitehall Cenotaph

Rolls of Honour

The usual portrayal of the public’s reaction to the outbreak of WW1 is one of patriotism and enthusiasm – after all it was going to be over by Christmas. From the outset many communities thought that they should record a list of everyone who had volunteered to go off and serve. The Roll of Honour as first envisaged was meant as a public thanks and acknowledgement to those who had volunteered to “join the colours”. It was certainly not intended solely as a record of those who died during the war, although that was what it came to mean after the war. Rolls of Honour were started in voluntary organisations, churches, schools, businesses and factories, and in the community at large.

As is described elsewhere, in Renton an army sergeant collected the names for a Roll of Honour in 1915. Contrast that with the councillors on Bonhill Parish Council who resolved to create one for the whole Parish, but actually made no attempt to do so. Renton acted while the Vale talked. By 1916 there were recriminations all round at Bonhill Parish Council meetings about why the Roll of Honour had not even been started, but still no action was taken – it never was. When a few years later it came to preparing a list of the names of the dead for the Parish War Memorial the people of the Vale knew better than to leave it to the Parish Councillors and they themselves became involved in collecting the names.

To a certain extent as the war went on the war-time Rolls of Honour were hijacked by the recruitment campaigners who presented them as a badge of honour. For instance Renton’s Roll of Honour was created so that it could be entered in a national newspaper competition titled “Britain’s Bravest Village” which was run to encourage volunteering. However, that should not detract from the obvious pride which people took in creating these Rolls during the war as a tribute to the serving soldiers. To-day at least two of these war-time Rolls of Honour have survived in the Vale listing people who served, as opposed to the names of men who were killed, although obviously some of the men on these Rolls of Honour were killed. Both are in the Masonic temples - in Renton and Alexandria. The one in Renton is a particularly fine example of a war-time Roll of Honour.

After the war the Roll of Honour took on a different meaning – it became a list of the men who had been killed during the war and that is the meaning most closely associated with the term Roll of Honour now. In the years immediately after the Armistice in 1918 few organisations in the Vale would have been without such Rolls of Honours commemorating members, employees, former pupils etc who had fallen. These were usually in the form of a list of names engraved on a tablet of stone or sometimes bronze and they would have been placed in a prominent place – e.g. in the reception area at the front office or in a church vestibule. It is believed that none of these have survived from the factories. Those placed in churches and public buildings have fared a little better, although some of them have also been lost because of closures. The one at the Vale of Leven Academy has been recreated and is listed below.

Local War Memorials

As WW1 ground on and the scale of the death and destruction caused by the modern industrial war machine increased remorselessly, the feeling grew amongst the public at large that there must be some public recognition and thanks for the sacrifices which young men were making. Although the numbers volunteering had fallen in the face of the reality of the horror at the front, it had been replaced by conscription from 1916 onwards. By 1917 therefore there was scarcely a family in the land who did not have someone serving in the forces and of course the scale of the losses meant that in virtually every street, road or hamlet a family had lost someone.

The first calls for some sort of National War Memorial started to appear about this time and these were soon followed by talk about suitable memorials at a local level. It was recognised that nothing could be done until the war was over, but by the time of the Armistice in November 1918 discussions were already quite advanced about what form war memorials should take,

On a national level the government decided in principle on a national memorial in London which it would pay for and it was also decided to create a Scottish National War Memorial in Edinburgh. The government made it clear, however, that it would not pay for local war memorials and that these should be the responsibility of local communities. As a result of the informal discussions which ad-hoc groups had been having throughout the country, there was an equally informal blueprint about how to create a local war memorial. This blueprint “emerged” from the public without any government involvement or direction.

It was so obviously such a practical and sensible plan that it was followed virtually everywhere, with some differences to take account of local circumstances. The plan had a few basic components:

- In each locality a local war memorial committee should be formed from members of the public. The forum for electing these committees would be a public meeting called for that specific purpose.

- It was the responsibility of these committees to raise the funds necessary to build the war memorials

- It was also their responsibility to decide on the nature of the war memorial preferably after public consultation, and to commission its building

- Each memorial would have a list of the local men who had died when serving with the colours no matter what form the memorial took. This list would be collected by the volunteers on the committee and made available for checking by the public who could thus try to ensure that no one was omitted.

- The committee should draw up a plan for the future maintenance of the memorial.

Vale War Memorials

This broad approach was followed in most places in the UK and the Vale was no exception.

We are fortunate that the records of the Bonhill Parish War Memorial Committee have survived in their entirety in Dumbarton Library which was also able to supply details of the erection of the Renton and Kilmaronock War memorials. So far we have been unable to find out anything about the Luss memorial, other than the names which are on it.

The names of all of those who appear on the WW1 sections of the four memorials are listed below. The totals are as follows:

- Bonhill Parish, 363 names

- Kilmaronock, 22 names

- Luss, 14 names

- Renton, 160 names

Total number of names = 559

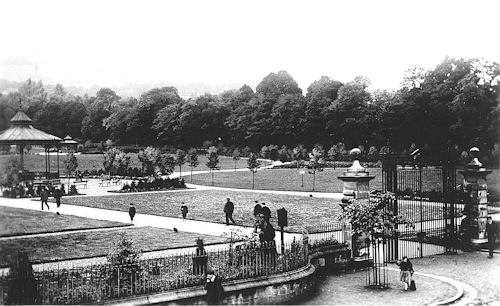

Christie Park before the War memorial was built (Click to Enlarge)

These Numbers are Not the Whole Story

559 is the total number of names of men killed in WW1 which appear on the 4 local memorials, but it is not the whole story. Firstly, many men died of their wounds after the closing date for inclusion on the war memorials and we have the names of some Renton men in that category. Secondly, for whatever reasons, some men never made it onto the lists and a cross check with the Vale of Leven Academy War Memorial provides further names. Thirdly, there are some double entries on the Bonhill Parish Memorial and we highlight these. Fourthly, there was no restriction on the number of war memorials on which a person’s name may appear and there are a number of people who appear on both the Renton and Alexandria Memorials and perhaps also the Kilmaronock Memorial.

The number of 559 men killed is therefore a little high when one considers the double entries, but in fact these are more than offset by the omissions from the official records which the War Memorial Committees were able to correct.

No Official Records

Finally, there are a number of men whose names appear on the local War Memorials but for whom there are no records in official sources. These official sources are:

- “Soldiers Who Died in the Great War” which was a War Department publication produced in the early 1920s which aimed to list by Regiment all those killed in WW1. It seems to have based its work on regimental / battalion / unit records and it is these records which are incomplete in many respects.

- The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, which are still being updated on a regular basis.

- The records kept by the Scottish National War Memorial.

This absence of information is no reflection on the quality of work carried out by these organisations, but it is a very negative comment on the state of the Army’s records of the soldiers serving at the front. The main reason for this was the absence of good record keeping in the battle zone, and by “battle zone” is meant not just the front line trenches where keeping accurate records would have been virtually impossible even if it had been given a priority, but the bases a few miles behind the front line. These were camps, usually consisting of wooden huts, typically about 5 miles or more behind the front lines, which were meant to be beyond the range of the German guns. Front line units rotated between these camps and the front line trenches – typically units operated a system of serving for 1 or 2 weeks in the front line trenches and then 1 or 2 weeks resting in the battle zone bases, although that did vary during major battles. Personal details of each soldier were kept there in these bases. (Full rest and recreation took place much further to the rear, usually even beyond where the high command based itself, and that was well out of harm’s way.)

During a battle, the troops in the trenches did their own accounting of losses at each lull in the fighting, which usually meant at the end of each day when darkness had fallen. Surviving soldiers would try to record what had happened to whom and compile a list of losses – known dead, wounded, captured and of course those of whom there was no longer any visible sign but whom their comrades had seen in a position where a shell had landed and who knew that they had been blown to bits. It was from these trench-based tallies that the daily Casualty Lists were prepared and sent up the chain of command to eventually appear in the newspapers. It was vital to commanders, of course, to know how many soldiers were available to them at the end of each phase of the fighting – at that stage they didn’t have to know who they were.

In the trenches, however, everyone was in this together - officers, NCO’s and men - and everyone felt it a duty to look out for their comrades of all ranks, particularly their fallen comrades, so that they could send messages back to a casualty’s family. We shall see in later Sections that particularly in the first 2 years of the War, many Vale people were to learn of their men folk being wounded, killed, captured or missing from letters from comrades still at the front or visits from comrades on leave or home to recuperate from wounds. The Lennox Herald had appeals virtually every week from local families for news of a soldier that they hadn’t heard from; as often as not it turned out that the soldier had been killed. As the war dragged on the War Department became more competent in sending out telegrams about the dead, wounded and missing but all of these were based on reports coming from the front.

What makes the failings concerning personal records indefensible is that it was not universal. Many regiments and units – across the whole of the Army perhaps even the majority of units - did keep very good records. In particular the forces from Australia and Canada, and many English regiments seem to have been able to keep track of the personal details of all the men of all ranks who served in the front line. However, the Scottish regiments performed poorly: almost without exception, they did not know names, addresses, next of kin, age and place of birth etc of all of their men serving at the front.

It’s hard to say now why Scottish units should have been poor at record keeping. It is true that casualty rates were higher in Scottish regiments than in many other units and maybe that placed a greater strain on resources. It’s also true that most Scottish units had a much lesser proportion of locally-based officers than English regiments – the officer recruitment policy very much favoured public schoolboys, who were then, as now, a rare species in Scotland. So there was a cultural disjoint between some officers and their men in many Scottish units and that may have reduced the informal communications between them. There is some evidence of this even where records of a man do exist e.g. in the phonetic and thus incorrect spelling of names and addresses. This is definitely not to say that the non-local officers in Scottish units did not care about their men – as is said above, in the trenches everyone was in it together, so circumstances ensured that they did care. It just meant that it was harder for these officers to keep abreast of personal details of the men and therefore record-keeping perhaps did not seem so important.

The relatives of men who were posted “Missing”, which could mean anything from blown to pieces, disappeared under the mud, wounded in hospital but unidentified, or captured, suffered a very unhappy fate – an extended period of not knowing but not wanting to give up hope of their man’s survival. The Army does deserve some sympathy in these cases because to begin with it just didn’t know what had happened except that a soldier was not present to answer a unit roll call after an attack, shelling, patrol etc. There was also a legal dimension to this. But it did come in for criticism from both soldiers and relatives, particularly after the Armistice, for not confirming much more quickly the deaths of soldiers whom their comrades knew – in many cases they had seen it happen - had been blown to bits or drowned in the mud. Some families did not receive confirmation of their loved-one’s death until 1921-22, although no body had been found and the death could have been admitted when it happened, years before.

So the question arises, given that there are a number of gaps in the official records, how did the local War Memorial Committees manage to fill in the omissions? The answer is a very simple one – at a local level, the information was almost always common knowledge. In the towns and villages of the Vale every street had a number of soldiers serving at the front and there was a keen awareness of the fate of each and every one of them in almost every household. In the two rural communities the news travelled every bit as fast. So when the Committees came to collecting the names, the teams in each ward could fill most of the lists right away, in most cases from their next of kin. The ministers and priests provided additional information, as did the one teacher we have been able to identify as being on the Alexandria Committee – David Balls headmaster of Jamestown School.