The Beggar Earl of Bonhill

William Graham, 8th Earl of Menteith, sold off his estate to his chief, the Marquis of Montrose, and to his nephew, Sir John Graham, 2nd Baronet of Gartmore to settle his debts, and the earldom fell dormant with his death in 1694.

William’s younger sister, Lady Elizabeth Graham, married Sir William Graham, 1st Baronet of Gartmore. They had a son, Sir John and a daughter, Mary, who married James Hodge of Gladsmuir.

The Hodges had a daughter, also Mary, who married her cousin, William Graham, a Writer to the Signet. He was the son of Walter Graham of Gallingad, younger brother of Sir William, and it was their 2nd son, William, born around 1704, who became the Beggar Earl.

William, who was uncle of the famous Scottish miniaturist, John Bogle, studied medicine at Edinburgh, but in 1744, he took it into his head that he was rightful Earl of Menteith and accordingly presented himself at the election of Scottish peers claiming “the right to vote”. He voted five times at the Election of Peers of Scotland between 1744 and 1761, after which, in 1762, his assumption of the dignities was prohibited by order of the House of Lords.

Despite his claim being disallowed, he continued to use the title for the remainder of his life and wandered as a beggar throughout the region. (Interestingly, his niece, Mary, sister of the miniaturist, styled herself “Lady Mary Bogle” until her death in 1781.)

It can be demonstrated, however, that William Graham, without doubt did descend from the Earls of Menteith, as both his mother and his father (from the 1st Earl) were scions of that noble lineage.

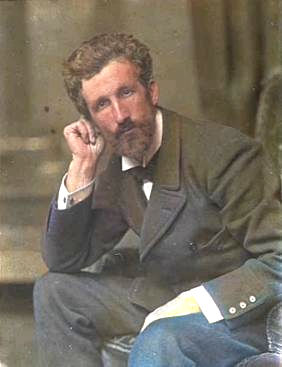

He was the author R.B. Cunninghame Graham’s first cousin five times removed and is one of the legendary characters of family lore. Cunninghame Graham, who was clearly fascinated by him, published his beautifully poetic short story, “The Beggar Earl” in The English Review (July 1913) and later included it in his anthology A Hatchment. In it he recreates a route he himself had ridden many times between Gartmore and Ardoch.

He was the author R.B. Cunninghame Graham’s first cousin five times removed and is one of the legendary characters of family lore. Cunninghame Graham, who was clearly fascinated by him, published his beautifully poetic short story, “The Beggar Earl” in The English Review (July 1913) and later included it in his anthology A Hatchment. In it he recreates a route he himself had ridden many times between Gartmore and Ardoch.

For a brief season he had been well known in Edinburgh. In 1744, when he was studying medicine, he suddenly appeared at the election of a Scottish peer and told the assembly who he was, and claimed the right to vote… From that time until his death, he never dropped his claim, attending all the elections of a Scottish peer till he got weary of the game… Once more he came into the public view, in the year 1747, when he published his rare pamphlet, “The Fatal Consequences of National Discord”, dedicated to the Prince of Wales. In it he says “that there can be no unity without religion and virtue in a state" (The publication remains in print).

Over the wild track on Dumbarton Moor, and past the waterfall at the head of the glen of Galingad, he and his pony must have wandered many times, reflecting that the lands he passed over should have been his own, for he was really Earl of Menteith by right and by descent, no matter though his fellow peers refused to recognize him…

The Beggar Earl died in a ditch in Bonhill, Vale of Leven, on 30th June 1783, and his funeral and burial were paid for by his nephew and surviving niece, John and Grizel Bogle. The receipt, dated 20th August, is signed by the Bonhill Kirk Session Clerk of the day, John Alexander.

The following is the full text of Cunninghame Graham's story of the Beggar Earl from his short story collection. A Hatchment published in 1913.

THE BEGGAR EARL

Many a shadowy figure has flitted through the

valley of Menteith. Just as the vale itself is

full of shadows, shadows that leave no traces

of their passage, but, whilst they last, seem just

as real as are the hills themselves, so not a few

of those who have lived in it seem unsubstantial

and as illusive as a ghost.

Many a shadowy figure has flitted through the

valley of Menteith. Just as the vale itself is

full of shadows, shadows that leave no traces

of their passage, but, whilst they last, seem just

as real as are the hills themselves, so not a few

of those who have lived in it seem unsubstantial

and as illusive as a ghost.

Perhaps less real, for if a man detects a spectre with that interior vision dear to the Highlanders and to all mystics. Highland or Lowland, or from whatever land they be, he has as surely seen it, for himself, as if the phantasm was pictured on the retina of the exterior eye.

Pixies, trolls, and fairies, the men of peace, the dwellers in the Fairy Hill that opens upon Hallowe'en alone, and from which issues a long train, bringing with them our long-lost vicar Kirke of Aberfoyle. True Thomas, and the rest of all the mortals who forsook their porridge three times a day, for the love of some elf queen, and have remained as flies embedded in the amber of tradition, are in a yay prosaic. Men have imagined them, ending them with their own qualities, just as they have endued their gods with jealousy and hate.

Those born in the ordinary, but miraculous, fashion of mankind, who live apparently by bread alone, and yet remain beings apart, not touched by praise, ambition, or any of the things that move their fellows, are the true fairies after all.

Such a one was the beggar earl. All his long life he lacked advancement, finding it only at the last, as he died, like a cadger's pony, by a dykeside in the snow. That kind of death keeps a man's memory fresh.

Few can tell to-day where or in what manner died his ancestors — the mail-clad knights who fought at Flodden, counselled kings, with the half- Highland cunning of their race, and generally opposed the Southrons, who, impotent to conquer us in war, yet have filched from us most of our national character by the soft arts of peace. A mouldering slab of free- stone here and there, a nameless statue of a Crusader with his crossed feet resting upon his dog, in the ebenezerised cathedral of Dunblane ; a little castle on a little reedy island in a bulrush-circled lake, some time-stained parchments in old monuments preserve their memory, ... to those who care for memories, a futile and a disappearing race.

His is preserved in snow. Nothing is more enduring than the snow. It falls, and straight all is transfigured. All suffers a chromatic change : that which was black or red, brown, yellow or dark grey, is changed to white, so white that it remains for ever stamped on the mind, and one recalls the landscape, with its fairy woods, its stiff, dead streams, its suffering trees and withered vegetation, as it was on that day.

So has the recollection of the beggar earl remained, a legend, and all his humble life, his struggles and his fixed, foolish purpose been forgotten ; leaving his death as it were embalmed in something of itself so perishable that it has had no time to die.

No mere success, the most vulgar thing that a man can endure, would have been so lasting, for men resent success and strive to stifle it under their applause, lauding the result, the better to belittle all the means. His life was not especially eventful, still less mysterious, for the poor play out their part in public, and a greater mystic than himself has said, "The poor make no noise."

Someone who knew him said he was "a little man ; a little clean man, that went round about through the country. He never saw him act wrong. . . . He was just a man asking charity. He went into farmhouses and asked for victuals; what they would give him; and into gentlemen's houses."

This little picture, drawn unconsciously, shows us the man he was after ill-fortune overtook him. For a brief season he had been well known in Edinburgh. In 1744, when he was studying medicine, he suddenly appeared at the election of a Scottish peer and told the assembly who he was, and claimed the right to vote.

From that time till his death, he never dropped his claim, attending all elections of a Scottish peer till he got weary of the game. Then disillusion fell on him, and he withdrew to beg his bread, and wander up and down his earldom and the neighbouring lands, until his death.

Once more he came into public view, in the year 1747, when he published his rare pamphlet, The Fatal Consequences of Discord, dedicated to the Prince of Wales. In it he says " that there can be no true unity without religion and virtue in a State."

This marks him as a man designed by nature

to be poor, for unity and virtue are not commodities that command a ready sale. He had not any special gift, but faith, and

that perhaps sustained him in his wanderings.

Perhaps he may have thought that he

would sit some day in a celestial senate, and

this belief consoled him for his rejection by an

earthly house of peers. One thing is certain, even had the House of Lords, that disallowed

his claim, although he voted several years in

Edinburgh, approved him as a peer, it would

not have convinced him of his right one atom

more; for if a man is happy in conviction, he

had it to the full.

It is said he bore about with him papers and pedigrees that he would never sell. No bartering of the crown for him, even for bread. A little, grey, clean-looking man, mounted upon an old white pony, falling by degrees into most abject poverty and still respected for his up rightness, and perhaps a little for his ancestry, for in those days that which to us is but a mockery, was real, just as some things which with us are valued, in those days would have been ridiculous.

So through the valley of Menteith, along the Endrick, and by Loch Lomond side, past the old church at Kilmaronock, through Gartocharn, and up and down the Leven, he took his pilgrimage.

Over the wild track on the Dumbarton moor, and past the waterfall at the head of the glen of Galingad, he and his pony must have wandered many times, reflecting that the lands he passed over should have been all his own, for he was really Earl of Menteith by right and by descent, no matter though his fellow peers refused to recognize him. He talked at first, in any house he came to, of his rights, and people having little news to distract them in those days, were no doubt pleased to hear him and to inveigh against injustice in the way that those who had themselves received it all their lives are always pleased to talk.

So does a goaded ox lower his head and

whisk his tail, and then, after a glance thrown

at his fellow, strain once again upon the yoke.

Then, when the novelty was over they would

receive his stories with less interest, driving him back upon himself, until most likely he

bore his wrongs about with him, just as a

pedlar bears his pack, in silence, and alone.

So did he, when the first efforts to obtain his

title and his rights had spent their force,

quit Edinburgh as it had been a city of

the plague when there was any election of a peer.

Whilst he was wandering up and down the

parishes of Kilmaronock and of Port, Scotland

was all convulsed with the late rising of '45.

Parties of soldiers, and bands of Highlanders,

retreating to the north, must have passed by him

daily, and yet he never seems to have had the

inclination to change sides. Staunch in his

allegiance to the Government, and with a faith

well grounded in the Protestant Succession, as

his pamphlet shows, most probably he was a

Church and State man, as he would have said,

up to his dying day.

Of such, as far as kings and rulers are concerned, are the elect, and thrones are founded on this unquestioning belief, more strongly than

on armies or in Courts. As the years passed, and he still wandered

up and down Menteith, losing by degrees the

little culture that his studies had implanted in him when he attended the Edinburgh schools,

the farmers must have begun to treat him, first

as one of themselves, and then just as they

would have treated any other wandering beggar

man. Still, on the few occasions when he had

to write a letter he always signed "Menteith," especially to begging letters, and the signature, no doubt, consoled him many a time for a

refusal of his plea.

Few could have known all the traditions of the district as did the wandering earl ; but he most probably, living amongst them, thought them not in the least remarkable, for it needs time and distance to make old legends interesting.

He and his pony must have been familiar figures on the roads, and when he came to a wild moorland farm, no doubt they welcomed him, expecting news from the outside world, and were a little disappointed when he sat silent in the settle, gazing into the smouldering peats, brooding upon his wrongs.

At such times, most likely he drew out his cherished papers from his wallet and pored upon them, though he must long ago have known them all by heart, and as he read them all his pride in his old lineage revived, and the long day upon hill tracks may have seemed light to him as he sat nodding by the fire. His hosts, with the old-fashioned hospitality of those times, would set before him a great bowl of porridge, which he must often only have eaten for good manners' sake, and then gone off to sleep beside his pony on the straw.

How many years he wandered through the mosses and the hills, how many times he saw the shaws in April green upon the Fairy Hill, or the red glow upon the moor in autumn, is not quite clear ; but all the time he never once forsook his wanderings. Offers were made him, by many of his friends, to settle down ; but either the free life held something for him that no mere dwelling in a house could give, or else he thought himself more likely to attain his object by being always on the road, travelling, as it were, like a Knight of the Holy Grail, towards some goal unseen that fascinated him, still always further on.

No doubt the darksome thickets by loch

sides, in which he and his pony must have

passed so many summer nights, were pleasanter

than a smoke - infested Highland shieling.

Sleeping alone in them he could hear all the mysterious voices of the night ; hear wild ducks

whirring overhead, the cries of herons in the

early morning, the splash made by the rising

trout, and watch the mist at dawn creeping

upon the water as he lay huddled in his

plaid.

All our old tracks, so long disused, but visible

to those who look for such things, by their

white stones, on which so many generations

of brogue-clad feet have passed, and by the

dark green grass that marks them as they

meander across uplands or through the valleys,

he must have known as well as did the drovers

coming from the north. Lone wells, that lie forgotten nowadays, but

of which then the passers-by all knew and

drank from, he too had drunk from, lying upon

his chest, and with his beard floating like seaweed in the water as he lay.

Mists must have shrouded him, as he rode

through the hills, and out of them strange faces

must have peered, terrible and fantastic to a

man alone and cut off from mankind. Possibly to him the faces seemed familiar and

more kindly than were those he generally saw

upon his pilgrimage. If there were fairies

seated on the green knolls, he must have seemed to them one of themselves, for certainly

he was a man of peace.

Cold, wind and rain and snow must have beat on him as they do upon a tree, but not for that did he once stay his wanderings up and down. As age drew on him it was observed that by degrees he seldom left his native parish, Kilmaronock, where he was known and understood by all.

There is a tract of moorland, high-lying and bleak, from which at the top you see Loch Lomond and its islands lying out as in a map beneath. The grey Inch Cailleach, and dark Inch Murren with its yews float in the foreground like hulks of ships, and the black rock of Balmaha rises above a little reedy bay. Just at the bleakest part of the bare moor the wandering earl was seen by some returning drovers on a cold winter's night. Light snow was falling, and as they passed him on the wild track that leads down to the vale of Leven, huddled up on his pony, they spoke to him, but he returned no answer, and passed on into the storm. All night it snowed, and in the morning, when the heritors were coming to the old kirk of Bonhill parish, they found him with his back against a dry stone dyke, and his beloved parchments in his hand.

Not

far away his old white pony, with the reins

dangling round his feet, stood shivering, and

in the snow where he had thrust his muzzle

deeply down to seek the grass were some faint

stains of blood.